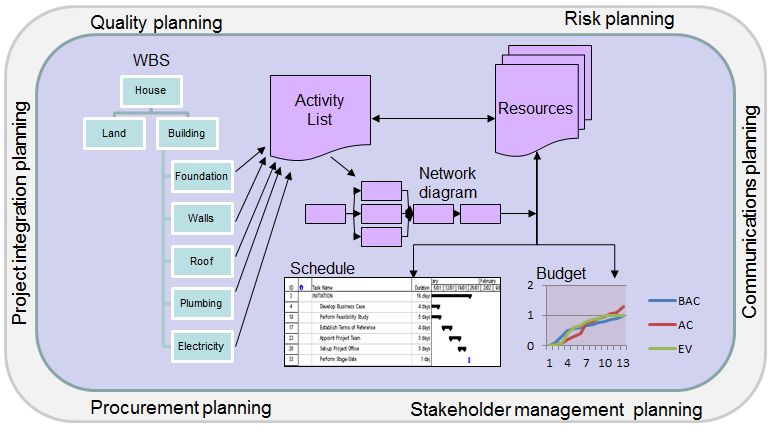

So we have compiled a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS). Great! – so what? How does this help us? How can we use this to get to a realistic budget for our project? Let’s start at the beginning.

From Need to WBS.

The main ingredient for identifying what is required from the project is to identify the project’s stakeholders. Easier said than done – there are only a potential of almost 7,3 billion stakeholders out there. The trick is to identify those stakeholders that most probably can and will influence our project. But that’s another story and let’s assume that we got this one covered. Once we have identified our key stakeholders we can find out what they need from the project. We can even be very efficient and unpack the needs into project objectives, the project objectives into requirements and magically get all key stakeholders to agree upon these requirements. At the end of the day we need to be able to define what this project is all about. That top block of the WBS. Call it what you will - the end objective, scope statement, work to be done or whatever.

From WBS to work package

Once we have identified the highest level of the WBS we can start figuring out what all the work is that needs to be done in order to ensure that we meet all the requirements of our stakeholders. We therefore start unpacking this top block into lower levels - always asking “what does this block consist of?” and the answer giving us the next level of detail. We can continue with this exercise until we get to the point where it does not make sense to unpack the lowest level block any more – sometimes called the Work Package level. We have reached the level where we can quite easily define what this little portion of the project is all about, give it to someone to do and monitor that it gets done properly.

From Work Package to Activity

The problem with a work package is that we all think that we agree what we mean by it while in essence each of us only agree on our own version of the truth! In order to ensure that we all agree on the same version of the truth we need to unpack the work packages into the activities required to do the work. This we normally call a WBS dictionary. There are other things we should also define in the WBS dictionary such as a more comprehensive description of the work package, the skills requirement, the acceptance criteria, etc. The main objective from a planning perspective is that we need to get to a list of all the activities required to complete the project.

From Activity to Network diagram

What is the minimum we need to sort out in which order we are going to do the work? We need the activity, its duration (that may depend on the specific activity effort required and the number resources available) and the logic – for instance which activity must be done before, after or together with which one. We can now start putting the network diagram together. Why do we need this Network diagram? – Because it would be quite handy to know how long it will take us to complete the project and which string or strings of the activities will determine this duration. If activity C can only be done after activity B is completed and activity B can only be done once activity A is completed we obviously need to keep a keen eye on activity A, B and C to ensure we get it all done in time!

From Network diagram to project schedule

If we know the logical order in which the activities need to be executed, the resources required for each activity, when these resources are available, when we will be working on the project and when not, etc., it is quite easy to calculate the exact dates on which each activity is planned to start and be completed. These dates, and especially the final date, is what our key stakeholders are so interested in. It is normally here were all the fun and games begin as the stakeholders sometimes believe these dates are cast in concrete while in real life they are our best guesses of multiple aspects that can influence these dates. But we need some order and therefore we agree to stick to these dates.

From project schedule to budget

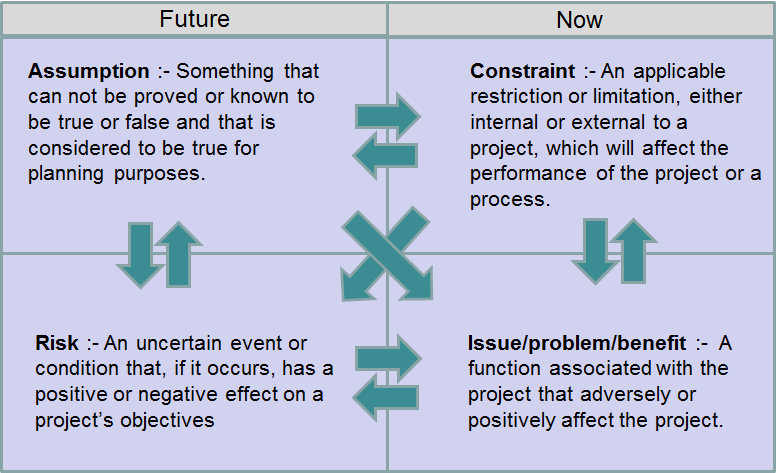

Knowing when every activity will be executed, which resources (human, equipment, material, etc.) will be needed and what the cost of each of the resources are puts us in the position to calculate how much each activity will cost us. We can also now roll these cost up to phase and project level and presto – we have half a project budget. The other half is that we also need to figure out how much money we need when on the project – a spending cash flow projection. For this we need the project schedule. Once we know how much the project is going to cost us and at what rate we are going to spend the money we are in a better position to control the project cost. Only a better position – not total control as there are these little inconveniences on projects we call change requests, risks, issues, and anything else Murphy can think of to spice up our lives that can play havoc with our estimates.

The short cut

With the help of project management and scheduling software tools we have become used to rolling most of these steps into one. It’s quite nice to quickly hop onto the software tool and start defining the activities, linking them together, assigning the resources and printing the WBS, schedule, budget, etc. - only to realize that we forgot to define who the stakeholders are. Not that they are important – they are only the reason for our project!

From Need to WBS.

The main ingredient for identifying what is required from the project is to identify the project’s stakeholders. Easier said than done – there are only a potential of almost 7,3 billion stakeholders out there. The trick is to identify those stakeholders that most probably can and will influence our project. But that’s another story and let’s assume that we got this one covered. Once we have identified our key stakeholders we can find out what they need from the project. We can even be very efficient and unpack the needs into project objectives, the project objectives into requirements and magically get all key stakeholders to agree upon these requirements. At the end of the day we need to be able to define what this project is all about. That top block of the WBS. Call it what you will - the end objective, scope statement, work to be done or whatever.

From WBS to work package

Once we have identified the highest level of the WBS we can start figuring out what all the work is that needs to be done in order to ensure that we meet all the requirements of our stakeholders. We therefore start unpacking this top block into lower levels - always asking “what does this block consist of?” and the answer giving us the next level of detail. We can continue with this exercise until we get to the point where it does not make sense to unpack the lowest level block any more – sometimes called the Work Package level. We have reached the level where we can quite easily define what this little portion of the project is all about, give it to someone to do and monitor that it gets done properly.

From Work Package to Activity

The problem with a work package is that we all think that we agree what we mean by it while in essence each of us only agree on our own version of the truth! In order to ensure that we all agree on the same version of the truth we need to unpack the work packages into the activities required to do the work. This we normally call a WBS dictionary. There are other things we should also define in the WBS dictionary such as a more comprehensive description of the work package, the skills requirement, the acceptance criteria, etc. The main objective from a planning perspective is that we need to get to a list of all the activities required to complete the project.

From Activity to Network diagram

What is the minimum we need to sort out in which order we are going to do the work? We need the activity, its duration (that may depend on the specific activity effort required and the number resources available) and the logic – for instance which activity must be done before, after or together with which one. We can now start putting the network diagram together. Why do we need this Network diagram? – Because it would be quite handy to know how long it will take us to complete the project and which string or strings of the activities will determine this duration. If activity C can only be done after activity B is completed and activity B can only be done once activity A is completed we obviously need to keep a keen eye on activity A, B and C to ensure we get it all done in time!

From Network diagram to project schedule

If we know the logical order in which the activities need to be executed, the resources required for each activity, when these resources are available, when we will be working on the project and when not, etc., it is quite easy to calculate the exact dates on which each activity is planned to start and be completed. These dates, and especially the final date, is what our key stakeholders are so interested in. It is normally here were all the fun and games begin as the stakeholders sometimes believe these dates are cast in concrete while in real life they are our best guesses of multiple aspects that can influence these dates. But we need some order and therefore we agree to stick to these dates.

From project schedule to budget

Knowing when every activity will be executed, which resources (human, equipment, material, etc.) will be needed and what the cost of each of the resources are puts us in the position to calculate how much each activity will cost us. We can also now roll these cost up to phase and project level and presto – we have half a project budget. The other half is that we also need to figure out how much money we need when on the project – a spending cash flow projection. For this we need the project schedule. Once we know how much the project is going to cost us and at what rate we are going to spend the money we are in a better position to control the project cost. Only a better position – not total control as there are these little inconveniences on projects we call change requests, risks, issues, and anything else Murphy can think of to spice up our lives that can play havoc with our estimates.

The short cut

With the help of project management and scheduling software tools we have become used to rolling most of these steps into one. It’s quite nice to quickly hop onto the software tool and start defining the activities, linking them together, assigning the resources and printing the WBS, schedule, budget, etc. - only to realize that we forgot to define who the stakeholders are. Not that they are important – they are only the reason for our project!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed